(Note: the article below was first written by me for the Ratcliffe College Old Boys magazine in 2004.)

The History and Aviation Heritage of Ratcliffe Aerodrome 1930-1950.

There can be little doubt that aviation was one of the most dramatic developments during the twentieth century. In today’s world, the lives of individuals as diverse as the poorest refugee or the richest billionaire are dependant on aircraft for the global transportation of freight and passengers in timescales of hours, rather than months as in the previous ship dependant era.

Thus, it might not seem surprising, that aviation has become

a highly documented topic. People are just as fascinated today with the mystery

of flight as were the crowds who cheered at the first great achievements of

crossing the Channel or flying across the

|

| Remains of the former hangars and clubhouse in 2004 |

It is, therefore, very apt that a vibrant and historic aviation legacy that has lay dormant for over fifty years amongst the dilapidated farm buildings and windswept fields that stretch north along the Fosse Way between Ratcliffe College and the neighbouring golf course, should be finally released to the honour and memory of those who created our aerodrome’s legacy and to the benefit of the future generations who it may inspire.

Central to everything is William Lindsay Everard, as there

would be no story to tell without this dynamic philanthropist. The Everard family ran a successful

Leicestershire Brewery and Sir Lindsay, who lived at Ratcliffe Hall opposite

the school was the MP for Melton Mowbray. In addition he also held many

committee positions such as President of the Leicestershire Aero Club.

|

| Sir Lindsay on the right presenting a model flying cup. |

Although he, himself, never became a pilot, he was very

passionate about the need for aviation development and in 1930 he began the

construction of his own aerodrome on the lands he owned directly to the north

of

At that time the young female aviator, Amy Johnson, had just

completed her solo flight from

Sir Lindsay managed to find a last minute stand-in in the

form of the Director of Civil Aviation who was Sir Sefton Brancker, but

possibly due to Sir Lindsay’s persuasive personality, Amy Johnson flew up from

Indeed the day was not without its other excitements including air races, formation displays and even a demonstration of air power in which 3 RAF aircraft “bombed” Chinese pirates with staged explosions suitable for the occasion. However, the finale was not the end of the excitement, as one of the 100 aircraft attending the Pageant crashed on take off narrowly missing departing spectators’ cars leaving through the aerodrome gate. Fortunately no one was killed, although the wife of the pilot who was the passenger on board was freed from the wreckage and taken to hospital.

(Click on video link above to see Sir Sefton Brancker alongside Sir Lindsay opening Ratcliffe Aerodrome. Unfortunately no sound available.)

Looking back now, it must have been quite a sight for pupils

at Ratcliffe to have witnessed the thousands of cheering spectators running

across the airfield to surround the bright yellow Puss Moth aircraft landing

with Amy and Sir Sefton aboard, but although the Pageant was a success, tragedy

was to follow. In less than 4 weeks, Sir

Sefton, who had officially opened the aerodrome, was killed on the inaugural

flight of the R101 airship to

However, Ratcliffe aerodrome was then to settle down to what

was probably its golden years up to the start of the Second World War. During

this decade Sir Lindsay developed the aerodrome into one of the finest civil

aerodromes in the country. The club house facilities were extremely hospitable

including an open air swimming pool (still there today). First class

maintenance hangars were built to accommodate the full time engineer who looked

after Sir Lindsay’s various aircraft. Sir Lindsay also employed a series

personal pilots including another famous aviatrix named Winifred Spooner. His pilot

would fly him around

|

| Sir Lindsay third from left on a typical excursion with friends. |

Fetes and displays continued at Ratcliffe aerodrome during the inter-war years and the Ratcliffian records occasion of the boys from the school being taken up for flights in Sir Lindsay’s aircraft, even by Amy Johnson on her later visits up to Ratcliffe. It also records Sir Lindsay’s admiration at the high standard of aeronautical knowledge displayed by the pupils during their visits, however, this is not surprising as boarding on the boundary of one of the finest aerodromes in Britain must have been a schoolboys’ dream for many of the pupils, although maybe not for the clergy and parents.

Some of the galas were most unusual for the time, such as the night time displays utilising the aerodrome’s floodlight equipment and especially the high power mobile searchlight mounted on the chassis of an old Rolls Royce of Sir Lindsay. Other fetes were of a truly international nature, such as the Weekend Aerien in 1936 and the Federation Aeronautique Internationale visit the following year. These occasions would be hosted in style with a large marquee and a garden party atmosphere, often a display from an overseas aircraft and pilot would be enjoyed. Strange to realise that an aircraft with a swastika on the tail was flying over Ratcliffe as a welcome guest many years before others would return “uninvited”!

It is a fine example of the aviation spirit of this time

that a man running a textile machinery business in Thurmaston should suddenly

decide to start producing aircraft! However, the growing aviation interest at

the time had included the formation of the County Flying Club around the

In fact, he was impressed enough to arrange with the American parent company to build the aircraft under licence in his textile machinery works. The prototype differed from the American version in some respects due to the British aircraft regulations and was called a Taylorcraft Plus Model C. This was taken by road from the works to Ratcliffe aerodrome for final assembly and the historic maiden flight of the aircraft that was to become the Auster aircraft took place at Ratcliffe on 3rd May 1939.

It would only be a few months later that war with

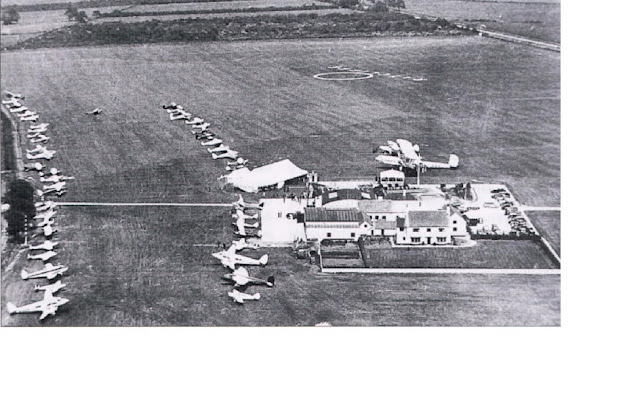

|

| ATA No 6 Ferry Pool at Ratcliffe WW2 |

This role was born out of the need to ferry newly produced

aircraft away from the factories as soon as they were ready. This task had

initially been done by Service pilots. However, the need for operational pilots

to be in the front line led to the formation of the Air Transport Auxiliary

(ATA) which initially utilised the flying skills of pilots not fit for RAF

service due to their age or some condition precluding combat duties. With the

creation of this organisation a logistical need for ATA ferry airfields spread

strategically across the country arose. With Ratcliffe’s central location and

excellent facilities it became an obvious choice and the ATA pipped the RAF to

the post to gain the agreement of Sir Lindsay for its use. Thus Ratcliffe

started a new career as No 6 Ferry Pool for the ATA; part of a network of

around 14 ATA Ferry pools stretching from Hamble in the South to Lossiemouth in

the far North, with White Waltham as the Head Quarters to the west of

|

| Peter George standing during a party night at Ratcliffe Ferry Pool. |

Sir Lindsay in his inimitable style had thrown open the

doors of his own large home at Ratcliffe Hall to accommodate many of the pilots

stationed at Ratcliffe during the war, others were billeted in the local

area. The ATA at Ratcliffe later became

a “mixed” pool consisting of both male and female pilots. Many of the pilots

were also from abroad, including many American volunteer pilots, all providing

a varied backdrop to the task in hand. Apparently, the Ratcliffe Ferry Pool

always retained a friendly atmosphere that it inherited from its previous club

existence, but the workload was considerable as the pilots moved thousands of

aircraft from the industrious

|

| Commander Frankie Francis is in the centre chair. |

One pilot stationed at Ratcliffe, J. E. Martens, for

example, moved 261

The aerodrome was not without its mishaps, however, and

accidents did occur and lives were lost. It

must have been a worry to the school that a potential crash might also

cause a catastrophic loss of life among the pupils given the close proximity to

the school and also the potential for the airfield to be a target for the

Luftwaffe. An account from Old Boy Basil d’Oliveira recalls how during the

standing for the school photograph in 1941, they were treated to a wonderful

low flying display by Old Ratcliffian George Saddington who was later on killed

in the war. He also recalls how a Hampden bomber overshot the runway in October

1941 and ended up in a blazing heap on the Fosse, fortunately no-one was

killed. Basil ran the aeroplane spotter club and could see many of the flights

into the aerodrome from the school tower. He estimates that some nights there

were over 50 aircraft spread out around the aerodrome perimeter and remembers

having to sleep in the gas tank shelters the night that

It was also in 1941 that Amy Johnson died, although not

stationed at Ratcliffe, she had joined the ATA and was ferrying an aircraft in

bad weather from

Her descent was seen by a Royal Navy ship patrolling close by. Although they got close to her, the sea was too rough for her to grasp the ropes and swept her away, the Captain ran aft and dived into the sea to reach her and although the crew could see him supporting her, they could not reach them. The body of Lt-Cdr Fletcher was found later, but Amy’s body was never recovered. Thus Amy Johnson became one of over 170 ATA personnel to lose their lives whilst serving in the ATA.

As the war progressed, the buildings surrounding the white

clubhouse grew as more facilities were added on as Ratcliffe’s workload

steadily increased. At one point the production of Spitfires at the Castle

Bromwich plant reached an incredible 320 aircraft per month. Ratcliffe’s

central position made it an ideal staging post and the aerodrome is credited

with having received every different type of RAF aircraft that it operated at

some time during the war. It even became responsible for the ferrying of

As the post war austerity began to ease in 1947, Sir Lindsay

again stepped in to help aviators in need, this time the homeless Leicester

Aero Club, which was looking for a new home to reform. Once again Ratcliffe

aerodrome reverberated to the sound of aircraft engines and once again

spectators flocked to see an annual display with a crowd of approximately 10000

people at the aerodrome in May 1949. However, this month also marked the

passing of the aerodrome’s great patron and with the death of Sir Lindsay, the

aerodrome land was soon put up for sale. The end of the aerodrome was marked by

a 16 aircraft flight around the local area and a party on

Having survived the risk of a direct accident for 20 years,

perhaps it is understandable that it was

|

| Old airfield boundary shown in red. |

Certainly comments in the Ratcliffian at the time refer to the risk posed by training aircraft in the hands of inexperienced pilots, however the Ratcliffian also looked forward to the increased area available for school playing fields. So, although, the motives to close the aerodrome were genuine and sincere, one cannot help wondering whether a slight inner guilt has caused the school to stay very low key about the historic role and wonderful heritage that it had brought to an end. Certainly in my 5 years as a pupil in the 1970s, no details were made forthcoming, and all I had was my own curiosity for the hangar buildings, where we pulled out our CCF Primary Glider on RAF cadet training afternoons. It was called the old airfield, but with the planting of the crops, I could never tell where landing areas lay or find out the history.

|

| Aerial photo taken by myself of former Ratcliffe Aerodrome site in 2004. |

Now, many years later, having listened to stories of some of the people involved, such as Peter George and Ann Wood-Kelly, who were both Ratcliffe ATA pilots and also having seen how proud the local people who worked at Auster factory are of their achievements, such as the 3000 aircraft they produced, it is time to re-address a balance. Time to give credit to the vision and forethought of Sir Lindsay Everard who set these events in motion and to be proud of our connection with Amy Johnson. Time to admire the skill and adaptability of a local community who with no prior experience became the country’s largest producer of light aeroplanes and finally, time to honour the courage and determination of a largely forgotten group of ATA pilots whose dedication and flying skill played an important role in the vital output of wartime aircraft.

|

| The commemorative plaque designed and commissioned by myself, which is now positioned in a main corridor of Ratcliffe College for the students to read. |

References:

Brief Glory

(The Story of the Air Transport Auxiliary) by E.C. Cheeseman.

The Forgotten Pilots by Lettice Curtis.

Aviation in Leicestershire and

Austers

(Nearly all you wanted to know) by The Intl Auster Club Heritage Group.

The Leicester Mercury and Auster Archives The Record Office, Wigston Magna, Leics.

(Thanks to Peter Stoddart)

Websites:

https://www.rafmuseum.org.uk/research/online-exhibitions/air-transport-auxiliary/

https://atamuseum.org/